Miriam Achu Rony is currently a Master’s student in Women’s Studies at TISS Mumbai. Mapping the gender dynamics played out in everyday experiences, she looks at gendered water vulnerabilities, and grassroots governance with fieldwork based in West Kochi.

“Every day begins with water—whether it’s boiling it, storing it, or walking in it after inundation.” (Field respondent, Palluruthy)

In West Kochi, it unfurls a dilemma – of scarcity and of spate of a basic element, water. Particularly, in regions of Palluruthy, Konam and Perumbadappu, water is a ubiquitous element, seen except in places where it’s most needed. Caught between this dilemma and the ‘almost paradox-like situation’ is ‘She’. Their life oscillates between either waking ‘for water’ or ‘into water’ – and sometimes, both.

(As the water starts to recede, most women start to clean their house. For women who rush to work, this water slows them down, both in their houses, and on their paths. : Credits – Reshma Prabin)

In official maps these are “water-stressed” zones. Its plans imagine neutral households, straight pipes and scheduled supply. But for women, their bodies and routines are shaped by it – dictated by the time when the tanker arrives, how far the nearest clean source is, and how fast they can mop after the floods recede –thus, their bodies carry the work no water plan has accounted for.

Specific Context of West Kochi

West Kochi is a low-lying estuarine region crisscrossed with natural and constructed ‘canaas’ (drainage channels). It experiences intense monsoon from June to September and summer from March to May. Because of its unique geography, tidal proximity and climatic peculiarity, the area is exposed to saltwater intrusion and waterlogging during high tides and intense rains. Yet during both summer and monsoon there might be no adequate amount of water reaching every household, the infrastructural reason cited for the same being, the area lies at the end of the water distribution network.

Thus it seeps into walls, floods streets, disappears from taps, and overflows from drains. It is stored in large basins and carried in plastic pots and waited on endlessly, in the daily wage households. Men often leave early to work, bypassing this reality. But for women, water remains inescapable – something to wake up for, walk through, collect, store and worry about. Ironically, both this drought and deluge is experienced in a city that is surrounded by water, but yet lacks access to clean, usable water. Over the years of balancing to the water’s rhythms, they have ‘adjusted’, ‘learnt to manage’, and have ‘inhaled these practices’ as their everyday life. The routine ascribed domestic work is currently a full-time crisis management system – disguised as care work, one that no urban plan has mapped.

Wading Through the Extremes: Embodied Water Labors

The experiences shared are not uniform across the entire region as the class and the geographical variances intersect and thereby distinguish these embodied experiences of women from one another. While financially stable households, both closer to the estuary-side areas and far from it, have invested in rainwater harvesting, large underground tanks, and filtration systems, women in low-lying, densely packed lanes survive on sheer will; it all hangs on one thread, “how will she be able to ‘manage’ water?”

The narratives are in itself a journey that communicate different themes; of coping with tidal inundation; struggling with scarcity and daily water collection; and subtle hints of the unequal terrain of water access. Moreover, across all lived experiences, what remains silent is the crisis of quality, crisis of access and crisis of governance in relation to water.

Reena (name changed), largely a home maker and who helps in family business of coconuts, has been settled here for more than 20 years with her house close to the banks of river, invests a lakh per year to level their courtyard to prevent the inflow of water and the articles carried by it, during both times of tide and the overflowing of the ‘canaa’ (drainage). A wall has been constructed to mitigate this intrusion, with government aid, on the banks. She also highlighted that because of the tidal inflow, especially during high tides and monsoon seasons, they ‘can’t grow a thing’ in their courtyard. If these exceptions are exempted, tidal inflow doesn’t really bother her, as it was never a headache to clean the house because water no longer enters their house. But there are other women, who had to completely dedicate their entire day’s routine to cleaning the house, where experiences vary, because a number of factors intersect in creating varied experiences.

In addition, to prevent the waste objects from entering into their courtyard, she has put palm leaves as an additional border, as the task of cleaning it is on her and her daughter-in-law’s shoulder.

(Efforts to balance the excess flow of water -palm leaf borders and walls. : Credits – Miriam Achu Rony)

Further, to ensure sufficient water supply to the house, they have also dug a well, into which they also store the entire rainwater, passed through a cloth (as a strainer), that falls on top of their roof. Yet, at the time when there is water shortage, they can’t use the indoor bathroom, because the nature of water changes. Since, it is difficult to use the toilet built outside the house at night, they keep 2 buckets of filtered water inside. In the initial years, when they didn’t have such coping mechanisms, life was difficult, as she came from a family where water was never a ‘scarce’ resource. Learning to ‘adjust’, changed her relation with water where every drop began to count.

Manju (name changed), who also practices as a Homeo Doctor in the area, shares that, despite having a huge underground storage tank and filtration system, she begins to stress out if water doesn’t come on time. Infact this was a pattern that all respondents shared. When they are given prior notices, they ‘plan’ how to use the existing storage. But if this is missed, the amount of anxiety and panic that accompanies, wouldn’t even make sense to the other inmates of the house. The water stress thus created is a constant companion of those who run the house, and quite to a great extent, this has been normalized as well.

“Getting anxious over water is also our daily life”. (Field respondent)

For the privileged, as Manju herself acknowledges, access and filtering amidst the water crisis, is relatively not as felt as the less privileged. The tanker lorries directly fill up their underground tank and they have a solar powered filtering system. But for people like Sheela, and others neither their monetary base allows them this nor the spaces they are in.

Sheela and Reshmi (names changed), also recollected their asymmetrical relation with water in the past, where they used to get up as early as 2 in the morning to fetch water from the public tap, waiting for hours, until they store enough and then go to shop and school, respectively. Being the head of the house, Sheela says it was natural for her to collect the water. But it was hard to manage when there were more members in the family. On one occasion she couldn’t attend a sent off meeting because she couldn’t bathe. The emotional cost of such nuanced experiences are never understood. Years down the line while she admits things are not as ‘scarier’ as it used to be, she asks when will we get free from this water stress? Currently, the chronic illness that has gotten hold of her has made conditions worse.

“I was unwell for a long time. Now I’m not physically fit enough to carry water. Since the councillor knows that, she gives some consideration and gets water delivered directly to the house tank.”

For Reshmi as well, right before her marriage, almost a decade back, and memories related to water were never a rosy picture. Her native home was in 18th division, as a school going girl, the task of fetching water was on her.

“Before marriage, when I was studying, we used to lose sleep waiting to collect water. This pipe served around 10–15 houses, so everyone had to collect water as soon as it arrived. Whoever reached first would get the water. So, we only got a limited amount. Everyone had to get their share. Back then, it was very difficult. We had to wake up at dawn, around 2 am and wait until water came. Sometimes, we had to stand there for hours. Because my mother used to go for work, I was the one who had to collect water most of the time. I had a brother – he would help occasionally, but still, I was the one mainly going to fetch water. When there was difficulty, men in the neighborhood would also help. Not that they didn’t – they knew their own household problems too, so they’d help once in a while…….During my student days, I had to wake up early and wait for water. Then I’d feel sleepy at school and didn’t have time to study. It was very tough. Now, there’s no such issue. I don’t have to stand and wait for water anymore”.

Though now, in her marital home she doesn’t face water scarcity as such, the situation in her native home hasn’t changed much:

“…….. but in the 18th division, nothing ever gets done. Just now, my father’s mother passed away last month, and after performing the death rituals, we had to take a bath. But there was no water available to bathe. That was last month, and even now there is still a severe water shortage there…… After a person passes away, we have to bathe and then enter the house as per the ritual, but there’s no good water. What we get is muddy water or yellowish water. So we were in a situation where we didn’t have water to bathe. Eventually, we contacted the councillor — not the one from that place, but our own (19th division) councillor — and arranged for a water tanker to be provided for bathing.”

Experiences also vary as women who lived in abundance come to a water scarce region as well as for women who lived in scarcity, but are gratefully relieved from the stress

There have been times Anisha (name changed), had to stay at her relatives house, because of water scarcity – specifically, during the ‘time of the month’, when coping without water was impossible. This is just ‘one side of water’ in her opinion, because the house right in front of her drowns by the evening, also ‘in water’. As she is a member of the residential committee, she says they have given a memorandum to the mayor and other higher authorities seeking permission for dredging the river, to mitigate the effect caused by this climatic phenomenon, which unfortunately, has not yet been realized.

The time and effort invested in cleaning the house every single dawn and the dusk because of the inundation as well as the time and effort invested in fetching the water, has significantly taken a toll on their physical health as well. Shyama (name changed – FGD participant), now in her late adulthood transition years, recollects from her past that earlier they used to carry their kids as well, as they go to collect water from the public tap, as nobody would be home. Even though situations have changed for the better now, it would still take time and effort to fetch water from the public tap and that’s the only source through which they collect water for drinking and cooking.

“The councillor said that water would be brought in a tanker lorry, mole (dear). But our house is in a narrow lane, so we have to carry it ourselves. Therefore, we rely on a public tap a little further away, so walking a bit is enough. From there, we bring water in 4–5 pots for drinking and cooking… If you ask, yes, every house has a pipe connection, but it only helps if water actually comes through those pipes.”

Lately, for the past two (June-July, 2025) weeks, the Kacherippady-Palluruthy area has been receiving continuous water supply. However, all participants vouch that the water is no good for drinking and cooking. Consequently, at present, they depend on canned drinking water which they buy for 100 rupees per 20 litre and have to give an advance of 500 rupees.

“These kids, you know—they all end up using this water (boiled and unboiled tap water) together. When they get thirsty, the children drink the water that’s kept at home. Adults aren’t always constantly watching what the kids are doing. Sometimes the water might be boiled, sometimes not. If it’s in bottles, at least they would understand it’s good for drinking. That’s why, even when there is no cash, people spend so much money on buying water.”

The households that run on daily wages find it extremely difficult to afford. Women in these houses limit their own water intake under these difficult times and ‘save’ it for other members of the house. The tragedy of the situation is also that they get humongous water bills as well, even if what their motor sucked up is fully air.

“For the past two weeks, we have been receiving water supply without interruption. However, the quality of water is extremely deteriorated. We can understand it by differentiating; good ‘and ‘bad’ water through taste, smell or by simply looking at it. You know it when you take it in a glass”.

Though people here have raised complaints, none of the interviewees or the FGD participants ever mentioned going to the consumer court and actually contesting the quality of the service received. Service providers, being liable to provide the basic necessities of life, entitled to all, are in alliance with the aim of the state and its service mechanism in place, to achieve improved living standards. Mariamma A. K’s (Associate Professor of Law) successful legal battle against KWA for billing her without water supply made headlines only a year back, in Kochi. She approached the Ernakulam District Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission and could get the order to arrest an Assistant Executive Engineer of the KWA who failed to comply with an earlier court order which directed him to pay compensation to her for the mental anguish and hardship endured as a result of the authority’s failure to supply drinking water. However, the question remains, who all possess the knowledge and are ready to give up their day’s wage to contest and take such an issue as grave as it is, to court.

Official documents rarely acknowledge that most women (daily wage labourers) skip a day or two’s work because of this water crisis.

“How will I go to work without bathing for 2 days, mole (dear)? If my spouse also doesn’t go, there will be nothing at home.”

If not all, at least for some families, water has been that element contributing to exacerbating the already existent poverty. Further, all the middle aged participants have an internalized notion that since men go out for work, they shouldn’t be burdened with household chores such as cleaning the house. The internalization of the nature of work is such that they believe ‘care work’ is supposed to stem from the women in the household only. Yet this quiet ‘adjustment’ becomes a gendered exhaustion that planning documents failed to register?

Blind Spots in Planning

Kochi Municipal Corporation’s Master plan – 2040, envisions a water secure, urbanized city -yet, in areas like Palluruthy the UN recommended 20–50 litres per person per day for drinking, cooking, and hygiene, remains aspirational. The plan appropriately details the inefficiencies in existing water supply networks– a demand-supply gap of 51.46 MLD, physical losses, treatment capacity limitations, tidal inflow, saline intrusion, and waterlogging. West Kochi’s service levels remain particularly poor, with many regions receiving only 15–20 hours of water supply per day and some experiencing levels as low as 50 LPCD (Litres Per Capita per Day). However, despite these important observations, the Plan lacks a nuanced understanding of how these issues are experienced unequally across social and spatial lines, particularly in terms of gender. While infrastructural inefficiencies are diagnosed well, a blind spot is fall upon who bears the cost of these gaps. Thus, it fails to see how these technical shortcomings materialize in people’s lives-especially women. The chronic water stress breathed in by women every day is invisibilised. When water is treated purely as an engineering concern, it lacks the lived social conditions of people and fails to ask who adjusts to this variability?

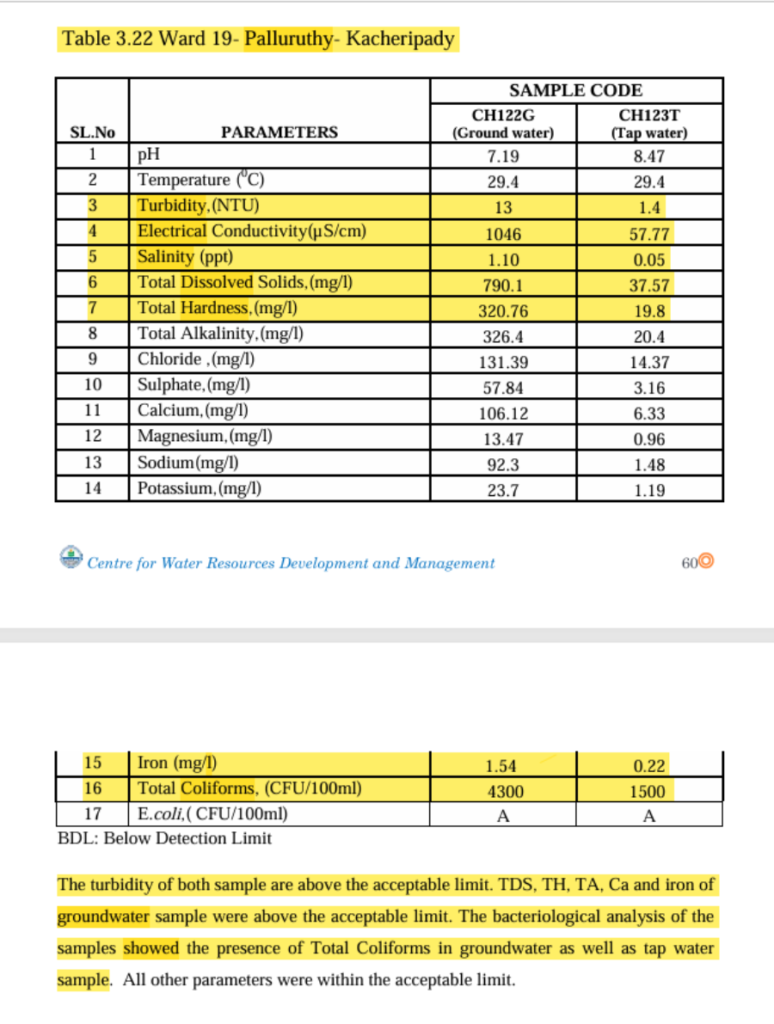

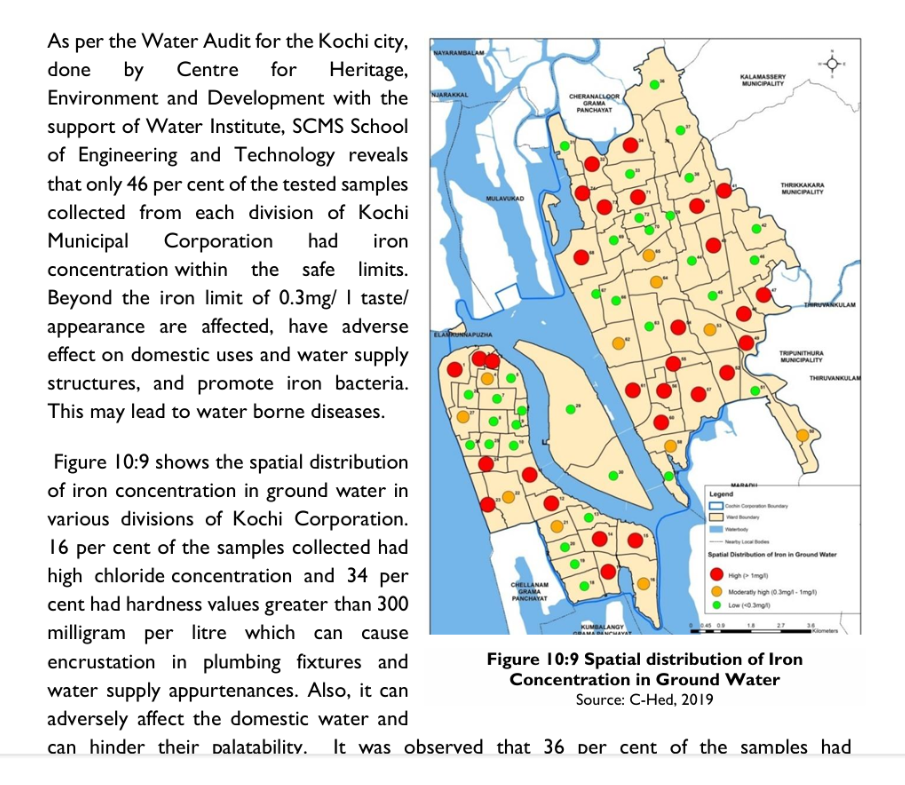

Scientific assessments like the Centre for Water Resource and Management report (2019), confirms high levels of turbidity, total coliforms and dissolved solids, not only in Palluruthy-Kacherippady, but also in adjacent regions. Yet quality monitoring and mitigation plans remain under-enforced.

(Source : CWRDM (2019) Report)

(Source: KMC Master plan (2023) 2040)

“Last week, the water was so bad that kids refused to drink it. Here, kids prefer other sources. There are people who struggle to afford gas just to boil water. Some don’t even boil – that’s how waterborne diseases spread. In fact I have many patients coming here because of the same.” (Manju)

Ensuring water quality is also the ‘responsibility/department’ of women in most households, though most measures taken in the underprivileged houses don’t go beyond boiling it. The quality of the water supplied remains central in all households and the primary concern of all ‘mothers’, no matter how big and small. This supposedly stems from the mother-nurturer- caregiver – axis. What would it mean to design water policy from the perspective of those who carry its burden? It would mean measuring not just availability, but accessibility, affordability, and effort. It would mean seeing women’s time and health as critical indicators. It would mean treating care—not just consumption—as central to water security.

Failures of Water Governance

Drinking water supply is not solely an engineering issue. As Lyla Mehta has put it, it is crucial to realize that water scarcity is both a ‘real’ and ‘constructed’ issue.

Even the residents here feels so:

If you move a little further, there are places where water always comes. We only have droughts at certain times. Even if we don’t get water here, there are other places nearby where we can get water. That is not because water is not coming. The problem is they redirect the connections to here and there. We have submitted complaints to the ward councilor itself. It’s after that we have started to receive regular water supply. Here, water is properly supplied till just in front of that doctor’s house. So, it is after shifting the connection line over there to here, which we began to get water. So when they don’t change these lines during water supply, then we don’t get water. Likewise, it is also unavailable when something gets stuck and blocks the water flow. (Field respondent)

“The councilor said that if we are not getting water, we can break the pipe in that way. But we said, there is no need for it…..the problem can be easily resolved if they open that valve. If they open that valve there, we will receive the water here. There’s a valve in that Kacherippady…when that valve was opened, during the previous councillor’s term, all the old public taps bursted. For two days, only turbulent, stagnant water came, but it became okay within two days…… Edakochi will only receive water if they close our line. We are not demanding for daily water supply, but they should at least ensure water supply in one day’s break. Everyone should get water. But they won’t even do that properly”. (FGD)

These are not merely anecdotes—they are diagnostics. Women understand the logic of the system, know which valve to open, and yet their knowledge is rarely legitimized within governance spaces.

“We have a pipe connection here, but in summer – April, May – we need a tanker lorry, at least 2–3 times. It’s brought through the councillor and directly filled into the tank.” (Field respondent)

Currently, a community-driven solution for either scarcity or spate doesn’t exist. Though there have been mobilization efforts with regard to the scarcity and many times women have taken the leadership to complain and lead a march tothe KWA office and the health office, it has been met with negligence. Or at times they contact the Ward Councillor to provide for separate water supply via tanker lorries during the crisis, which is delivered. However, so far all these efforts have promised only temporary reliefs. A permanent resolution of the problems is yet to be achieved. The technocratic, gender blind documents, though views it as a humanitarian issue, haven’t yet been able to see, not only the gender labour behind it, but also the gendered implications that arise from the same. When they approached their representative for covering the drainage, they were met with ignorance. They did not shy away from expressing their frustration.

“In Kochi, we keep hearing speeches saying “Kochi has progressed, progressed.” Where has it progressed? Such a smart city it is, huh! We are the ones lying at the very bottom of Kochi itself. When we went to the MLA to ask if something could be done to stop this flooding near our house, do you know what he said? “That’s the job of the Corporation, I can’t do anything about it.” Everyone comes here only when its election time, otherwise no one even steps in. Just watch, this time I’ll not allow even one person to enter my doorstep.” (FGD)

They have also proposed to dredge the river to ensure natural flow of water into the river, so as to reduce the water logging, but face so many delays in implementing it. Often people feel their problems are left unheard, as well as unseen. The problem remains unaddressed because the ‘authority’ fails to realize and capture these everyday gendered hardships and health hazards arising from it. These dismissals reflect not just apathy, but a deep disconnect between technocratic governance and embodied hardships. Or in some ways, the system has become accustomed to ‘squeezing the poor’ in multiple ways—charging for erratic water supply, failing to ensure its quality, and ultimately forcing vulnerable communities to bear the cost of medical treatment for water-borne diseases.

“When the tide comes, all this visible filth and the muck already lying around will enter this house. And it’s always us who clean it every day, again and again. If there’s some kind of permanent solution, it would be a big help. Just think about the sewer water entering the space where children play—it could lead to all kinds of illnesses, God knows. These kids play right in the middle of it without realizing the risks”. (FGD)

Apart from this, excess water flows in the area as the ‘canaa’ overflows. Along with not cleaning the silt regularly and people’s reckless behaviour of dumping waste in it, the narrowing of the canals as well has contributed to the water logging;“5-6 years ago they reduced its width. Only a few of us opposed it …I was the only woman who spoke against it. However, they didn’t pay attention to my words”. (Field Respondent)

Even the implications of maintenance (breaking pipes and laying new ones) are also felt on them, as the mud flows into their courtyard and they have to spend hours cleaning it. Essentially, a lion’s share of women’s labour goes into this cleaning work alone, which is often seen as an unproductive sphere, and hence, not paid attention.

What the Narratives Reveal?

The attempt was essentially to redraw the water map of Kochi, not by pipelines and tanks, but by tracing where women’s bodies move, strain, stretch and resist. These narratives, across West Kochi reveal water as more than a substance—it is a social relation, a burdened routine that is not yet identified as crisis, a source of both bodily discomfort and structural disenfranchisement. The themes emerging from these experiences travel from embodied labor, a form of hydro social inequality where multiple layers like monetary privilege, class, geography, and infrastructure contribute to widening it, to gendered governance failure.

If viewed from a gendered labour lens , all of these instances throw light on how women’s lives are shaped around water’s rhythms; how the two cannot be separated, as captured by Neimanis’s hydro feminism. Moreover, the gendered silence speaks volume here; water work is treated as routine, not recognized as a crisis. What is also left unacknowledged are the ways in which it causes both physical and mental discomfort: the former in relation to fetching and storing it and the latter, of the everyday anxiety of what if there’s no water tomorrow. Though Anisha says, now they receive prior alerts, if water supply is stopped abruptly, on occasions when they miss out, it creates a headache.

Intragenerational and intergenerational experiences are even more different as well, because many respondents acknowledged that all the houses have received house connections, thus, from easing the task of fetching it every single day, to only when motors can’t suck up water. Thus as hydro-feminism might find it right if argued, these women’s bodies more than being of water, are shaped by water injustice. Crucially, the study also highlights how when gendered voices and experiences are silenced in planning, it fails to deliver the most essential commodity primarily handled by women in the patriarchal household setup. If looked closely, the emotional cost borne by women, for instance that of skipping a gathering due to uncleanliness or that of staying at a relative’s home to maintain hygiene, is also left unacknowledged. These are light coping mechanisms that they practice to ‘adjust’. These instances show the extent to which experiences of water and sanitation are deeply gendered and require sensitivity in planning.

All these instances hint at what has been captured in concepts like Feminist Political Ecology – gender remains a critical variable in access, control and resource management. Though water is primarily handled by women, the price of it is paid by their spouses, who are in the productive sphere. It also highlights how it has little say in structures that determine its availability or quality

What is the possibility of gendered water governance or is there really a need for gendered water governance?

The themes decoded through the narratives clearly shows that water scarcity and excess are not gender-neutral crises. Even social reproduction is very much embedded in this. Even though they are active participants in complaints, petitions and resistance, their potentiality as a grassroot governance node, specifically in relation to water remains under-explored. Having a system as Kudumbashree already in place, its aptitude for the same, can be put into further reflection and be utilized.

Together, these themes expose how water scarcity and flooding are not gender-neutral crises. They are shaped by and reproduce everyday gendered hierarchies. Without recognizing this, policies will continue to address “pipes and pumps,” while ignoring the women who carry both water—and the crisis—on their backs.

Conclusion: Towards Feminist Water Justice

Water has been recognized as a fundamental right to human life by various judgments by both the Supreme Court (1991) and Kerala High court (1990). This reading together of lived experiences and policy documents from a feminist lens was also to suggest that water governance must be sensitive towards the hydro social realities. Recently, the KWA has made SUEZ their partner (Public Private Partnership model) in the system upgrade for Kochi City water supply. Reportedly, the aim is to enhance water availability and water quality for 7,00,000 people with emphasis on 24×7 pressurised water supply. What this promises to west Kochi, however, is unclear.

Way forward

Is there a way for a feminist water governance? If yes, what can be done as the initial steps to achieve it? What if water governance had a vernacular infrastructure that could potentially aid the water crisis? Is further decentralization possible for water governance?

As part of its’ Drink from Tap Mission, Odisha Government has similar issues at the ground level to address in the Puri city, erratic and unequal water supply, inconsistent pressure, high loss of Non-Revenue Water and frequent disruptions caused by the cyclones. It was even more challenging as the city only had 50% house connections and the rest relied on other sources bartering their time and effort in exchange for a pot of water. It rightly acknowledged the disconnection between the water supply authorities to the community. Community partnership for community led drinking water distribution management was a pitch in point in the implementation of the programme. Therefore, it reformed itself at the institutional level and launched the community partnership programme – Jalsaathi (Water Friend) which appointed members of Women Self- Help Group (performance linked incentive based) to bridge the gap between the public and the institution. In the Jalsaathi model, a whole range of activities – meter reading, bill distribution, and revenue collection, along with being trained to carry out household level water quality indicator tests.

Although KWA doesn’t supply water on time, the bills reach right on time, shares the FGD participants. Therefore, even if not replicated in its entirety, the potential of incorporating Kudumbashree members in one aspect of water governance, that is in water quality testing in areas like West Kochi, can be definitely explored and be translated into the ground, provided that the state already claims it has trained 5000 Kudumbashree members in rural areas, in water quality testing in its 14th Five year plan. Strengthening their role can bridge the policy-practice divide, and be part of core water governance tasks. At the same time, their participation must not be mere tokenistic, but should move with due recognition to their agency. Or as an alternative, a possibility of establishing Water Councils as an all-inclusive group in the grassroot level of water stressed areas, wherein responsibility of both decision making and water quality testing are shared equitably, can also be explored, so that it doesn’t cater to further reinforce the ‘mother-nurturer-caregiver’ axis.

While global frameworks have identified the urgency of Gender mainstreaming in water policies and management, it is not reflected in local official documents yet. Therefore, in future formulation and planning, the frameworks given by IWRM (Integrated Water Resource Management) like gender and water policies (Tool A1.04) or, gender responsive budgeting in water management (Tool, D1.06) are possible guidelines. Another alternative framework for gender inclusivity in water governance is to explore how the central programme of “Women for Water, Water for Women” (Nari Shakti se Jal Shakthi approach) has been integrated. The LSGD (local Self-Government Department) claims about 938 Kudumbashree members from 18 urban local bodies in Kerala were part of the campaign. However, respondents in Palluruthy ward dismiss any knowledge of it. When the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), in collaboration with the Ministry’s National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM), launched this as part of Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), it was expected to make a significant stride towards inclusivity in water infrastructure. However, how much of it will effectively translate amidst KWA shaking hands together with SUEZ, is yet to be seen. Without such steps, the hidden costs of water vulnerabilities borne by women–in terms of time, health, emotional labour and unpaid care work – remain unaddressed in public planning. It is only by centering women’s lived experiences that water justice can truly flow.

The exploration was to offer a critical archive of gendered water vulnerability amidst drought and deluge. If governance continues to disregard these everyday rhythms of care, inequality will persist not only in pipelines, but in bodies. It is to realize that women’s labour becomes a parallel ‘distribution network’. What if budgets flowed through women’s groups instead of consultancy firms? Why not a decentralised approach for water governance? What if every policy draft began with: Who carried the water today, and why?

It’s an indictment—and an invitation. To reimagine not just how water flows, but how power does.