Drawing insights from a recent village-level study done by CSES, our Fellow Dr. Rakkee Thimothy writes on the problems and prospects of labour market behaviour of Malayali women. (The Malayalam version of this write has been published in True Copy Think) Image courtsey: Observer Research Foundation

This article is an enquiry into the low labour market participation of women in Kerala. One of the striking features of the much celebrated ‘Kerala development experience’ is high achievements made by both men and women in social and development indicators. However, when it comes to women’s labour market participation, the State lags. Not only does a low share of women are employed in Kerala, but a high share of women is unable to find a suitable job, and worse, many are not even seeking jobs. The latest data relating to the labour market provided by the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2018-19) conducted by the National Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India in June 2020 captures the severity of the situation. Among the 15-59 age group, while 78 per cent of males are either working or looking for a job, the corresponding figure for women is merely 35 per cent. In the same age group, while 74 per cent of males are employed, the share of women employed is 29 per cent. As we all know, unemployment is a major issue in Kerala—23 per cent of males remaining unemployed compared to 55 per cent of women reporting unemployment. The severity of unemployment becomes clear when one looks at the national average, which is merely 17 per cent unemployed among men and women.

Considering the high educational attainment of women, their lower participation in employment is problematic. A growing body of literature captures the influence of cultural norms on household and individual decision-making that determine individuals’ entry and exit to the labour market, specifically in the case of women. A major reason cited for the low participation of women in the labour market, particularly youth, is to fulfil childcare and household responsibilities. However, it is problematic to assume that such responsibilities should be shouldered entirely by women. Such duties are imposed on women as an accepted norm in most cases, often not considering women’s job preference or employment aspirations. As secondary data sources are not suitable to understand social norms that influence and determine labour market outcomes at the micro-level, the Centre for Socio-economic and Environmental Studies (CSES), Kochi, has undertaken research to unpack reasons for the low participation of women in Kerala in the labour market.

Some of the key questions posed by the research are as follows: What determines the labour market entry and exit of individuals? Do there exist any difference in job search pattern across gender? Does marriage affect the labour market outcomes of women? How do household responsibilities, norms like jobs suitable for men and women interfere with an individual’s choice of ‘preferred jobs’? What made women move out of the labour force—stop looking/seeking a job? We try to find answers to these questions through a village study in Maneed, Ernakulam district, among youth populations (those in the age group of 18-40 years). Major findings from the research are noted below:

Study Findings Corroborates the Secondary Data on Employment

Low Participation in Work

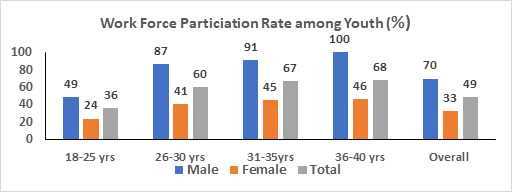

The proportion of young women (aged 18-40 years) who are employed is less than half that of men- 33 per cent for women and 70 per cent for men. The work participation rate for men is 100 per cent in the 36-40 age group and 91 per cent in the age group of 31-35 years. Thus, almost all the young men aged above 30 years are employed while only 45 per cent of the women in the same age group are employed. Even in the 26-30 age group, 87 per cent of the men are employed as against just 41 per cent women.

Women Unemployment: A Pressing Problem

A significant difference exists in the unemployment rate between men and women. As against 13 per cent for men, the unemployment rate for women is 43 per cent. The unemployment among men is mainly in the age group 18-25; it is 9 per cent in the 31-35 year age group and nil in the 36-40 year age group. On the other hand, the unemployment rate among women is as high as 40 per cent in the 31-35 age group and 27 per cent among the 36-40 age group.

| Age Group | 18-25 yrs | 26-30 yrs | 31-35 yrs | 36-40 yrs | Overall |

| Male | 31 | 11 | 9 | – | 13 |

| Female | 54 | 49 | 40 | 27 | 43 |

| Total | 41 | 32 | 23 | 13 | 27 |

Neither working nor looking for a job

What is extremely disturbing is a pattern of women quitting the labour market—neither working nor searching for a job. While almost all men aged above 26 years are either employed or searching for jobs, therefore, are part of the labour force. As against this, 20 per cent of women in the age group 26-30 years, 25 per cent in the age group 31-35 years, and 27 per cent in the 36-40 age group are not seeking employment even though they are not currently employed.

Social Conditioning and Women’s Labour Market Entry

Several women cited marriage and family-related responsibilities limiting their job prospects. When asked about the reasons for unemployment, 58 per cent of the women who are currently unemployed but are seeking employment reported that after the marriage decision of partner and other family members, childbirth and family responsibilities adversely affected their employment prospects. Such reasons were cited only 4 per cent of the unemployed men.

After marriage, it is always the women who had to relocate to her husband’s workplace, irrespective of the job held by her. Some of the currently unemployed youth held a job previously. When they were asked to give the reasons to quit the previous job, 61 per cent of females reported the marriage and/family responsibilities as a reason against just 6 per cent of men reporting so. Sandhya, 26 years old married female, shares her story:

“I am a B. Tech graduate and was working in an IT firm. After marriage, my husband insisted me to take a break for six months. I was not ready, but I had to accept finally as there was no one to support.”- says Sandhya.

About one-third (32%) of the women who changed jobs in the past did so because of family responsibilities/marriage, while the corresponding proportion for men is only 4 per cent. Remya, a 37-year-old housewife, is not able to continue her job because of household responsibilities.

“After marriage, it became my responsibility to look after my paralysed mother-in-law. There is no scope for me to seek or go for jobs. I am a B. Com graduate and was working in the finance sector before marriage. I can’t go for work in the current situation as I am burdened with handling the household duties along with taking care of my sick mother in law”-Remya says.

Job Preference

Previous studies have suggested that the strong preference for government jobs contributes to high unemployment among the youth in Kerala. But only 12 per cent of unemployed women and 8 per cent of unemployed men expressed a preference for government jobs. Inclination towards self-employment or for starting own enterprises is low among youths. Restrictions imposed on women regarding location, nature of work, work timing etc., by the spouse or his family also constrains her employment choices. The CSES research points to a strong preference to obtain a job near their home among female job seekers, perhaps conditioned by social and cultural norms. Neenu, a 28-year old female, illustrated the change marriage brought into her profession. A graduate in General Nursing, Neenu is now working as a saleswoman in a medical shop near her husband’s home. After marriage, she did not even seek nursing jobs.

“It is not possible to go for night duty these days as I have a two year old kid. That is why I started searching for daytime work. I have not been in the nursing profession for the past two and a half years and doubt if I will be able to rejoin,”– she says.

While three-fourths of the male job seekers are open to working anywhere, nearly three-fourths of female job seekers prefer a job near their current residence. This would essentially limit the scope of their job search, which, in turn, adversely affect their job prospects.

It is interesting to note that gender also determines what would be a preferred job for an individual. During the research, employed respondents were asked to reveal the merits of their current jobs. The financial benefit from the job, flexible work timings and job satisfaction were the common response from both males and females. However, balancing household responsibilities and proximity to the workplace have been cited as merits of the current job by a higher share of females. While it may appear that the strong job preference regarding location, work time, and nature of work is leading to high unemployment among women in Kerala, the real barrier is the social conditioning that burdens them with domestic responsibilities, for which the research stand testimony to.

Pattern of Job Search

A significant difference also exists in the intensity of job search by men and women. The unemployed youth who are currently searching for jobs were asked about the number of job applications they have submitted during the six months preceding the survey. While 57 per cent of women who are currently searching for jobs have not applied for a single job during the last six months, the corresponding proportion for men is only 24 per cent. This implies that unemployed men are more active in job search compared to unemployed women. In most cases, the low number of jobs applied by women is also because even applying for a job, they need to consider if the potential jobs meet the criteria set by their partners and family.

Towards Women Inclusive Labour Market

It is important to recognise that gender conditioning affects individuals’ aspirations and labour market outcomes, and very often, women are at the receiving end. A conscious effort is required to change the ‘male breadwinner model’ and accept that both males and females need to play an equal role in society and family. A major factor cited for women’s withdrawal from the labour market is to fulfil family and childcare responsibilities. There is a need to evaluate to what extent child and elderly care facilities in the State meet the requirements of working persons and develop a strategy to encourage greater participation of women in the labour force. This is important considering that the policies of the Government of Kerala, like Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Policy (2017) and the draft of the Kerala State Labour Policy (2017), have categorically stated a need to improve labour market outcomes, particularly of women.

Given that family duties hinder women’s entry into the labour market, it is important to create awareness among men to share household/caring duties. Yes, this sentiment was echoed by the Chief Minister of Kerala during the lockdown imposed in the State following the COVID-19 pandemic and, more recently, through the ‘Ini Venda Vittuveezhcha’ campaign by the Department of Women and Child Development, Kerala government. It is also important to focus on skill training/upgradation, job fairs targeting women, strengthening self-employment programmes or providing incentives to organisations that facilitate the re-entry of women into the labour market.